The Unitarian Universalist Service Committee advances human rights through grassroots collaborations.

By on November 29, 2018

Part 1: Kids in Tents in Tornillo, Texas

I slowed down the car as we approached the abandoned tollbooth, cautious about whether we were really allowed to enter the open gate, but no one was watching. As we passed through to the other side, we could see layers upon layers of metal fencing, wide empty fields, and a camper van with a hand-written sign, “Witness: Tornillo.” There were only two reasons why vehicles passed this rural Texas intersection. To the right, a remote port-of-entry to Mexico was used almost exclusively by trucks towing totaled cars across the border for parts. To the left, a steady stream of ICE buses, Border Patrol vans, and various workers entered and exited the tent city-style detention camp for immigrant children.

Joshua Rubin, who had been manning this 24-hour witness for almost a month now, exited the camper to greet us. I introduced myself: “Hannah Hafter, Senior Grassroots Organizer at the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee.” Beside me stood the first two out-of-town volunteers who came to El Paso through the UU College of Social Justice’s program to support an emergency shelter for arriving asylum-seekers recently opened by the Annunciation House.

The Tornillo facility, about 45 minutes outside El Paso, is officially designated for “unaccompanied minors” ages 13 to 17, but the vast majority of youth inside have family members in the United States eager to receive them. The huge increase of Central American unaccompanied minors under U.S. custody is not merely a result of increasing arrivals, but largely due to the merging of immigrant child welfare and ICE enforcement. As word spread that ICE was using these kids as bait—investigating not only the child’s direct sponsor, but also all members of the sponsor’s household for their immigration status and detaining everyone undocumented—the resulting fear kept many kids in Tornillo from reconnecting with families. In some cases they arrived on their own, seeking to reunite. In other cases, they were traveling with family members, but separated by Border Patrol.

The official story is that Tornillo is temporary, and will close by Christmas. But news got out that the contract had now been extended through March. During the one morning we spent at Tornillo, we watched construction vehicles entering, and a large tractor trailer delivering hundreds of metal rods and white tarp-like materials. It was easy to conclude that the tent camp for children is growing.

Sure enough, less than a week later I heard that the number of youth detained there rose from 1,300 to 2,500, and counting.

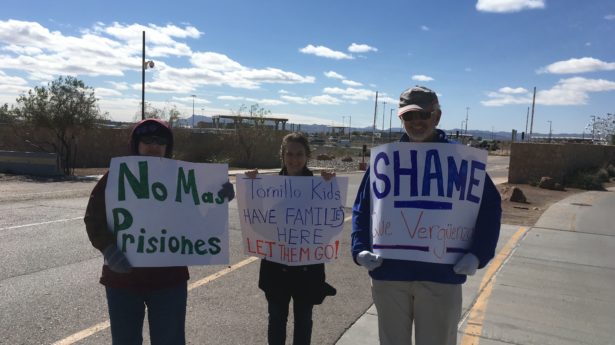

That morning the four of us stood in the bitter cold wind holding signs with messages for the kids in the buses and the drivers passing by. There was a strange power and powerlessness at once to holding up the signs for each passing bus—being somewhere no one was supposed to be, seeing what was supposed to be hidden from view, being seen watching. I wondered: How do we move Tornillo from out-of-sight-out-of-mind to a national outcry?

Photo Credit: Hannah Hafter