The Unitarian Universalist Service Committee advances human rights through grassroots collaborations.

Hurricane Harvey: Fear and Courage After the Storm

By Syma Mirza on February 20, 2018

In early December, nearly four months after Hurricane Harvey wreaked havoc along the Gulf Coast, Kathleen McTigue of the UU College of Social Justice and I traveled to Houston, Tex. to meet with Unitarian Universalist Service Committee (UUSC) partners providing disaster relief and recovery assistance to those affected by the storm. In line with UUSC’s commitment to grassroots collaboration, our grants to these groups target community-based organizations reaching populations that struggle to access mainstream relief and services.

Two such groups in Houston include Living Hope Wheelchair Association and Fe y Justicia Worker Center. Living Hope works at the intersection of immigration and disability rights, and Fe y Justicia (“Faith and Justice”) protects the rights of “second responders,” the mostly low-wage, immigrant workers performing a bulk of the city’s post-hurricane reconstruction work. We also met with Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (t.e.j.as.), an environmental justice organization working with the predominantly low-income, minority neighborhoods along the Houston Ship Channel.

Throughout the trip, we were reminded that natural disasters exacerbate existing inequalities. We also felt the heightened sense of fear among certain populations, particularly undocumented immigrants, in today’s political climate. Yet, even in the face of such daunting challenges, we also witnessed the courage and dignity of countless individuals still fighting for the rights of those worst affected by Harvey.

Exacerbated Inequalities: “We were already living in a disaster situation.”

Natural disasters around the world have demonstrated that low-income households and communities of color are disproportionately affected by extreme weather. Many of these communities reside in high-risk living conditions to begin with, whether due to the quality of their housing, poor infrastructure, or proximity to flood waters and pollution. In Houston, Harvey merely intensified these struggles. Structural barriers to accessing relief and services make longer-term recovery more difficult for the poor, racial minorities, immigrants, and those living with disabilities.

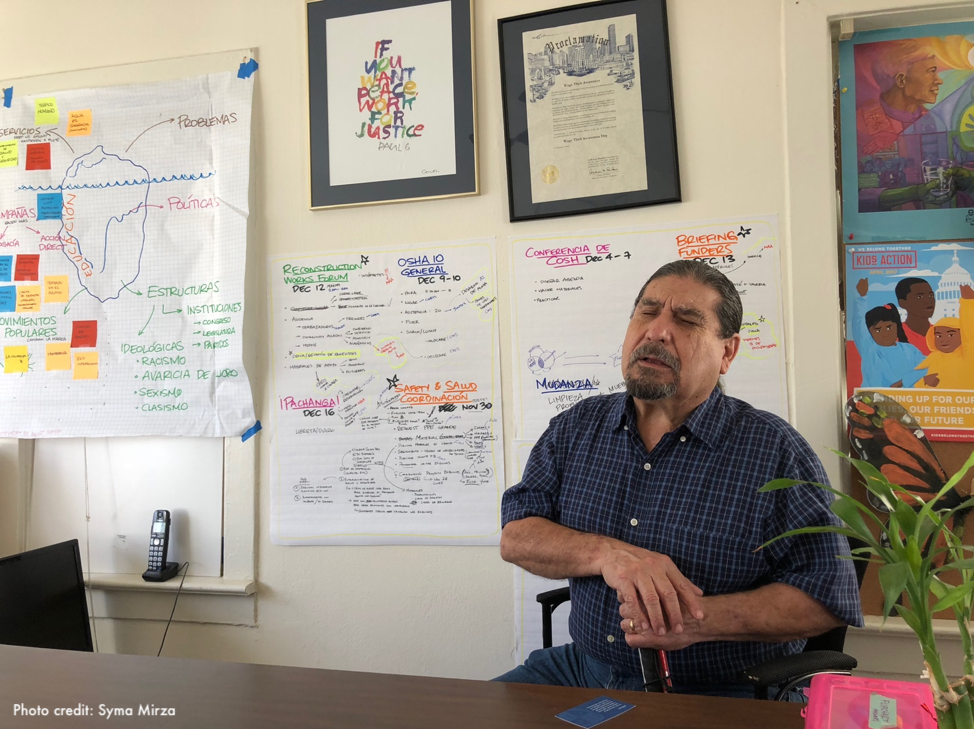

Living Hope Wheelchair Association works primarily with undocumented immigrants suffering from spinal cord injuries, most of which resulted from workplace accidents or crime. Its modest office consists of two rooms and a storage unit for medical supplies and a handicap-accessible vehicle. Many members are on constant medication, in regular pain, and in some cases, require dialysis, but very few have medical benefits. As Pancho Argüelles, Living Hope’s Executive Director, put it, “We were already living in a disaster situation with respect to health care, housing, transportation, and undocumented status,” before Harvey. After the storm, the organization’s members needed to replace electronic wheelchairs lost to flood waters, repair houses and wheelchair ramps, and raise financial assistance to cover medical, transportation, and basic living expenses.

Fear on Top of Fear

For the approximately 600,000 undocumented people living in Houston, limited access to medical benefits and health insurance, coupled with fear and mistrust of immigration authorities, have made them one of the most vulnerable populations after the storm. The majority of Fe y Justicia Worker Center’s constituency consists of undocumented immigrant workers. In the face of continued anti-immigrant political rhetoric and crackdowns by local police and immigration agencies, people have been scared to seek even the assistance and benefits for which they are eligible. This fear, on top of existing language and other accessibility barriers, has magnified needs and vulnerabilities after Harvey. Whether it is medical care for a sick child, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) benefits, or wages due, people must conduct a mental calculus to assess the risk of claiming their rights.

Fear and insecurity also leave people prone to abuse. In numerous cases, tenants have been afraid to push back against landlords who have failed to ensure safe living conditions or unfairly evicted residents at short notice. This additional layer of fear has also had a chilling effect on activism. Living Hope’s members are now less willing to travel for state-level advocacy through hostile counties between Houston and Austin out of fear that police may inquire about their immigration status. And while the storm has increased media interest in people’s stories and highlighted important needs and concerns, speaking to journalists and publicizing identifying details creates serious risks.

A Toxic Tour

The Houston area is home to the largest petrochemical complex in the United States and the second largest in the world. On our second day, t.e.j.a.s. took us on a “toxic tour” of various municipalities between Houston and Baytown, Tex. along the Houston Ship Channel, a key transport route for petrochemicals and other goods into the Gulf of Mexico. The torrential rains and ensuing floods from Harvey resulted in “a stew of toxic chemicals, sewage, debris and waste” that disproportionately impacted nearby neighborhoods, comprised primarily of low-income people of color. A long stretch of oil refineries, chemical plants, waste processing facilities, and other industrial plants borders the ship channel. Homes, schools, parks, and playgrounds, including Hartman Park shown here, sit in close proximity to many of these facilities, regularly exposing residents to harmful chemicals.

T.e.j.a.s. staff explained that childhood asthma and other respiratory ailments affect a significant portion of the local population. A 2007 University of Texas School of Public Health study reported that children living within two miles of the ship channel had a 56 percent higher incidence of leukemia than those ten miles away. In 2016, the Union of Concerned Scientists and t.e.j.as. published a report finding higher levels of toxicity from chemical exposure in east Houston than more affluent west Houston neighborhoods. Indeed, to us, the pollution was visible and palpable. In some areas we visited, the air smelled, and almost tasted, sickly sweet.

In the first week after Harvey, damaged oil refineries and facilities released over two million pounds of hazardous substances into the air. Flood waters also triggered the release of thousands of gallons of spilled petroleum. Neighborhood residents experienced headaches, sore throats, eye irritation, and nausea at greater rates than usual. While air and water pollution has been a longtime point of contention for frontline communities, Harvey magnified the problem.

Needs and Opportunities

In the face of these overwhelming challenges, t.e.j.a.s. and Living Hope both emphasized that Harvey brought not just urgent needs but rare opportunities. The storm has provided a chance to draw increased national attention to underreported problems. Local civil society is using Harvey as a catalyst to raise awareness, build coalitions, and call for reforms to address the structural reasons low-income and minority communities are so adversely impacted by disasters in the first place. Living Hope explained that it is using services and campaigns to build organizations and movements toward long-term change. It has activated its members, raised its voice, and reached a new level of visibility.

As recovery continues, UUSC is proud to support organizations working to address the needs of underserved communities following Harvey. We are especially grateful to the generous donors who made this work possible. Six months after the hurricane, thousands of people are still unable to return home or rebuild their lives in parts of Texas. But among those most affected by the storm, we are encouraged and inspired to see people overcoming fear and adversity with dedication, strength, and courage toward a just recovery for their communities.

Syma Mirza is a consultant supporting the Rights at Risk portfolio.