The Unitarian Universalist Service Committee advances human rights through grassroots collaborations.

Stories of Impact

1940, Marseille, France

By mid-1940, the Nazis had already taken control of Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France. World War II was taking severe tolls on human life throughout Europe, and not enough was being done to assist the thousands of people attempting to flee the mortal dangers of Nazi occupation.

Just months after the Unitarian Service Committee (USC) was officially founded, Martha and Waitstill Sharp were on the ground in Marseille. There, they first worked — successfully — to secure a trainload of condensed milk, in great demand to feed refugee babies in southern France. When Waitstill left for Lisbon to establish a new USC office, Martha remained in Marseille and worked with USC volunteer Helen Lowrie on a child emigration project that was a collaboration between USC and the United States Commission for the Care of European Children.

As told in Roots and Visions: The First Fifty Years of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, by Ghanda Di Figlia, “From September 15 until November 25, [Martha Sharp] and Helen Lowrie doggedly but diplomatically battled the various bureaucracies as they accumulated the exit visas, transit permits, and all the other papers necessary to arrange for the emigration of 27 children and 10 adults. Martha sailed from Lisbon in early December with two of the children and four of the adults. Ten days later, the other adults and the rest of the children followed.” The Sharps and their counterparts continued working throughout the war to bring relief to refugees throughout Europe.

“We were urgently pressed to do everything we could because we were afraid that we wouldn’t be able to accomplish what had to be done.”

—Martha Sharp

2014, Cebu, Philippines

In November 2013, Typhoon Haiyan, the strongest recorded storm to make landfall, devastated parts of the Philippines and killed more than 6,000 people. The region most affected by the storm already had 40 percent of its population living below the poverty line, and the storm wiped out the homes and livelihoods of countless farmers and fisherfolk. With lives upended, hundreds of thousands of people were left traumatized by the disaster.

In the aftermath of natural disasters, mental health is often overlooked — and dealing with trauma can be key to recovery for survivors. To meet this need, UUSC partnered with the Trauma Resource Institute (TRI) to train more than 40 community leaders in TRI’s Community Resiliency Model (CRM), which uses body-based skills that have proven successful in treating the symptoms of trauma, which are often debilitating.

The community leaders have gone on to spread the skills to thousands of survivors, including more than 1,000 schoolchildren. Rainera Lucero, who coordinates UUSC’s Philippines work, reports, “The CRM training makes a big difference in the way organizations address mental health. CRM’s approach to managing trauma has proven effective in bringing about strength and well-being in people. The CRM skills are empowering people and communities.” UUSC is also supporting partners in working with government agencies and universities to replicate this kind of trauma resiliency training throughout the country.

1970s, El Salvador

In the 1970s, UUSC supported grassroots empowerment of Salvadorans. Through funding Justicia y Paz (Justice and Peace), a newsletter created by a Salvadoran priest, UUSC helped provide literacy skills and raise political awareness among the campesinos, rural Salvadorans who had little access to education. After the 1977 massacre of hundreds of people protesting election results in San Salvador’s Plaza Libertad, UUSC asked Archbishop Oscar Romero how UUSC could help.

Dick Scobie, former UUSC president, describes the meeting: “We sat in his little room. He was a small gentle man. We said, ‘What can we do?’ And he said, ‘Tell the world, particularly tell the United States, what’s happening here, because we really need help badly and nobody knows what’s happening.’” Scobie and other UUSC staff met with Salvadorans who spoke of the massacre and terrible repression.

In response, UUSC sponsored fact-finding congressional delegations to El Salvador — the first by a private agency. In 1978, Rep. Robert Drinan was the first legislator to take part. Over the next decade, UUSC took over 30 members of Congress (from both houses) to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua to gain firsthand knowledge of conditions there. They spoke with peasant leaders, union members, the press and clergy, as well as refugees and government and U.S. embassy officials.

These delegations were instrumental in changing U.S. aid policy in Central America. “There’s just no doubt that a trip of this nature is exceedingly valuable,” said Representative Connie Morella (R-MD), a delegation participant. These trips helped legislators look at how they could address the injustices from their leadership positions. Rep. Morella continued, “Resolutions that have to do with human rights abuses requiring investigation, questioning where the money that we’re sending to El Salvador is directed — is it really directed to helping with the development of the country? Is it economic development? Does it go to the people?”

“I’m convinced that our work with Congress accelerated the shift away from seeking a military solution to seeking a political solutions.”

—Dick Scobie, former UUSC president

2012, California, United States

In 2008, UUSC began working on the ground with partners in California to establish state-level legal recognition of the human right to water. The road to passing a new law was long, but September 2012 brought sweet victory: Governor Jerry Brown signed the California Human Right to Water Act (A.B. 685) into law.

In addition to recognizing that safe and affordable water is a basic human right, the landmark bill requires state agencies to consider that right as they develop policy likely to impact water service. This is good news for more than 11.5 million Californians — most in rural, low-income communities of color — who don’t have access to safe and affordable water for drinking, cooking, and bathing.

Throughout the lead-up to this historic achievement, UUSC worked with the Community Water Center (CWC), the UU Legislative Ministry of California, the Environmental Justice Coalition for Water, and other partners in the Safe Water Alliance. Together, the organizations published op-eds, rounded up their members to take action, and worked hard to include community voices in the process.

Maria Herrera, CWC’s community advocacy director, recalled listening to the legislative debate: “I thought of my own family living in Seville, Calif., of my father laboring in the fields during the day and coming home in the evenings to Global South infrastructure and contaminated tap water. This issue is personal for me.”

Since the law passed, UUSC has been partnering with Safe Water Alliance organizations to ensure effective implementation of the law. In a state that has 12 percent of U.S. population, this sets an important precedent and provides a model for other states and countries.

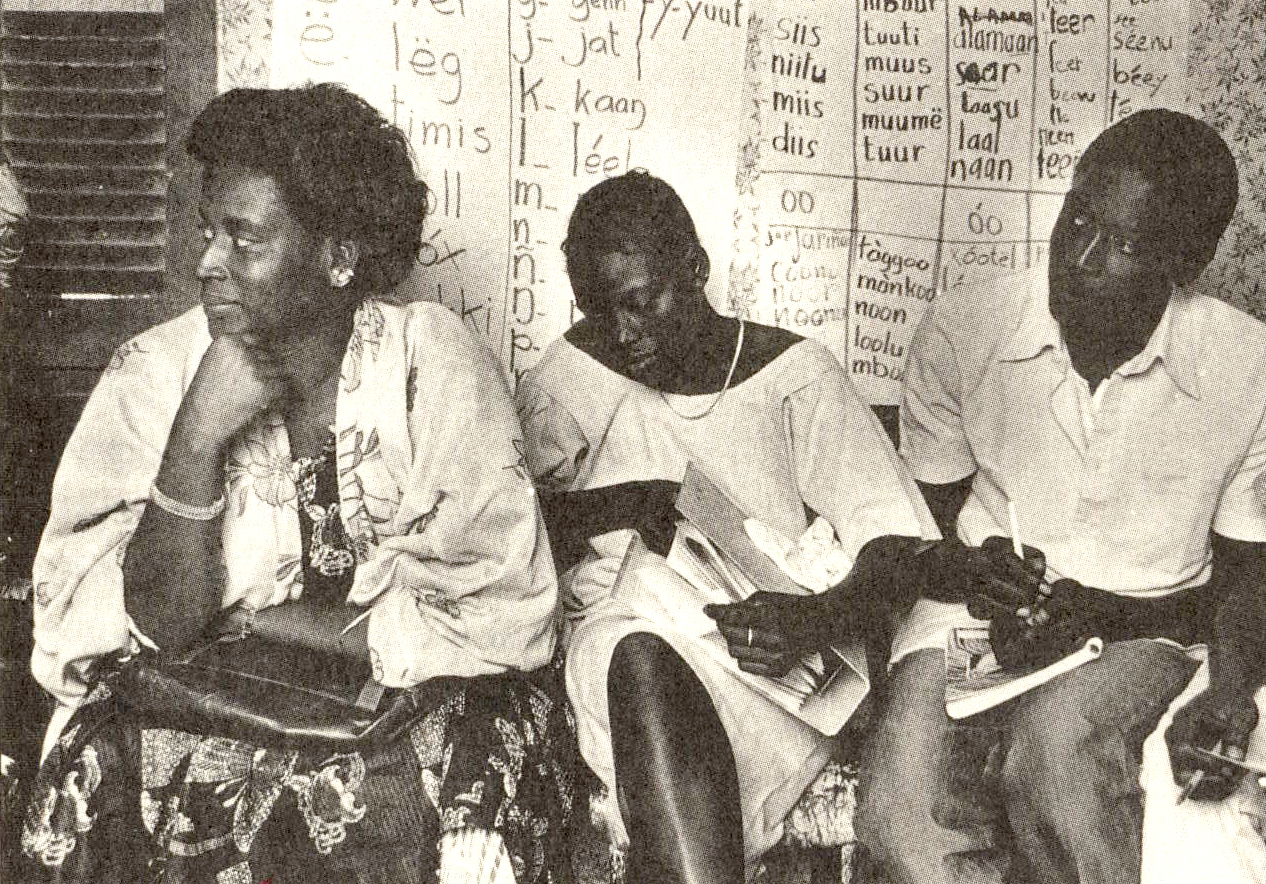

1980s, Dakar, Senegal

In 1984, UUSC established ties with the Federation of Senegalese Women’s Associations (FAFS). This group of women’s organizations, founded in 1977, focused on the needs of women who were migrating from the countryside to the capital city of Dakar in search of employment.

With UUSC’s support, FAFS embarked on its first major project: a center where young migrants could acclimate to city life and access literacy classes, family life education, and job skills training. Directed by FAFS Treasurer Fatou Diakhaté, the center also grew to serve young women who grew up in the city.

UUSC’s relationship with FAFS was the beginning of a new approach. As Ghanda Di Figlia wrote in Roots and Visions: “UUSC came to regard itself less as a facilitator for specific programs and more as a partner in the strengthening of democratic organizations that define and work on their own priorities. Indigenous self-help groups that form in response to local conditions know their own needs and are acutely aware of the economic, social, and political terrain in which they work.”

As their work evolved, FAFS discovered that many of the migrants actually wanted to return to the countryside. FAFS put a plan into action with UUSC’s help: They started a farm outside of Dakar, where the young women could learn the agricultural skills they need to make a living in their villages. When the women returned home, FAFS representatives helped them transition back and offered ongoing guidance.

As UUSC’s work with FAFS continued, the group grew to include 154 local, regional, and national organizations by 1989. Diakhaté was considered a leader in development and women’s issues. FAFS’s institutional purpose — “to unite women’s groups with similar ideas and create among them links of solidarity and mutual assistance and to promote Senegalese women in the economic, social and cultural realm” — was stronger than ever.

2010s, Central Plateau, Haiti

Just weeks after the 2010 earthquake hit Port-au-Prince, UUSC was on the ground assessing needs of the people being overlooked in the wake of the devastating natural disaster. With the majority of aid concentrated in the capital city, UUSC began working with the Papaye Peasant Movement (MPP) in the Central Plateau, where thousands of families had fled to when their homes and livelihoods were destroyed.

Founded over 40 years ago, MPP is a nationwide grassroots organization with more than 60,000 members, the majority of whom are small farmers grouped into cooperatives. They use sustainable organic growing methods, advance food sovereignty, and stand up for the rights of women and small farmers.

From the start of the partnership, UUSC was passionate about Haitians themselves leading the recovery in ways that supported their own vision. UUSC asked questions, listened to the answers, and helped MPP hone plans for how they would like to support families in the wake of the earthquake — and that’s how the first eco-village was born.

An innovative model pioneered by MPP and UUSC, each eco-village is home to 10 displaced families who have started new lives as small farmers. With six villages — two made possible by UUSC and the other four funded by the Presbyterian Disaster Assistance — now in place, 60 families have shelter and the means to feed themselves and generate sustainable livelihoods. UUSC has also helped MPP build a school to serve the children of the eco-villages. Families receive agricultural training and ongoing community support from MPP — and they are thriving.

“An eye-to-eye partnership is a partnership that offers respect and mutuality, that appreciates diversity, that gives support, that is open to teaching each other. The commonality of our partners is that we treat them as equals . . . . We don’t subsume them; we don’t make them part of us. We join them.”

—Atema Eclai, former UUSC programs director

1980s, United States

UUSC has a long history of engaging with its constituents to organize collective action that advances human rights. While the institutional structures and efficacy of these efforts have fluctuated over the years, UUSC’s partnership with its supporters showed marked growth — with some exciting results — in the 1980s.

As Ghanda Di Figlia wrote in Roots and Visions: The First Fifty Years of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee:

“The Volunteer Network (formerly the Volunteer Service Corps) stabilized by the mid-1980s to about 500 members. In 1980, volunteer William Lucero of Topeka, Kansas, gathered a group of like-minded people into an association to oppose death penalty legislation. This group, which was credited with an important role in the successful campaign to keep Kansas from becoming a death penalty state, became the first UUSC Unit. By the end of the decade, UUSC had 13 Units. Unlike the short-lived Action Leagues of the mid-1970s generated by [UUSC] staff, Units are grassroots entities, formed when members of the Volunteer Network in three or more congregations come together and petition UUSC for Unit status. UUSC provides each Unit with consultation, educational materials and a budget, and the Unit in turn brings the [UUSC] policy agenda out to the community.”

Today, that legacy continues in the form of the UUSC Justice-Building Program, which expands and deepens how UUSC works with individuals, clergy, religious educators, congregations, and groups to cultivate and harness the “human capital” needed to effectively champion justice on every level.

2005–08, Gulf Coast, United States

In September 2005, Hurricane Katrina brought catastrophic physical destruction, inept government response, and massive barriers to reconstruction. UUSC joined with the Unitarian Universalist Association and partners in Louisiana and Mississippi to grow the UU Gulf Coast Volunteer Program, which made significant strides in rebuilding with a spirit of justice.

The seed began at the Unitarian Church of Baton Rouge. Diana Dorroh, program director there, spoke about the outpouring of support: “As soon as we walked in the door, we discovered that the phone was ringing off the hook with UUs from all over the country wanting to come down and help.”

The program first put volunteers to work cleaning up debris and stripping homes of moldy interiors to save them from demolition. Highlights over several years included the following:

- Over 2,000 volunteers donated more than 57,000 hours of service to gut, repair, and rebuild more than 2,300 homes and community buildings.

- Volunteers participated in a orientation, guided by “A Dialogue on Race, Class, and Katrina,” developed by Jyaphia Christos-Rogers and Pat Callair, to deepen their understanding of the lives of Katrina survivors and to integrate that into rebuilding efforts.

- The volunteer program successfully transitioned to local management in 2008, under the New Orleans Rebirth Volunteer Program of the Greater New Orleans Unitarian Universalists, and is now spearheaded by the Center for Ethical Living and Social Justice Renewal.

Kim McDonald, UUSC’s former senior associate for education and action, said, “Every volunteer leaves New Orleans a different person and hopefully equipped with a basic understanding of how race, gender, and class have contributed to the problems in the New Orleans area. We are equipping them to be effective advocates for the Gulf when they return to their own communities.”

In 2008, Quo Vadis Breaux, then the new director of the New Orleans Rebirth Volunteer Program, highlighted the heart of the program: “Volunteers come to give, as well as to find that they have received the gifts of gratitude, knowledge, and the fellowship of standing in solidarity with residents and other volunteers.”

1970s, Mississippi and Massachusetts, United States

In the mid-1970s, UUSC made the most of developments in video technology to enable people to tell their stories through two projects in the U.S. South and Northeast.

As Ghanda Di Figlia wrote in Roots and Visions:

“The advent of portable half-inch video cameras and the high promise of community access to the airwaves over cable TV seemed to offer a great opportunity for innovation and local empowerment. The U.S. programs staff reasoned that people become dis-empowered when they rely on others (the mass media, establishment structures, etc.) to define their reality. If, on the other hand, people had the means to explore and define their reality and communicate their knowledge and concerns, they would be better able to control their lives and the conditions in which they live.”

In Boston, UUSC put cameras in the hands of youth to document school integration and promote racial understanding. “The Boston Video Access Center worked out of our basement on Beacon Street,” remembers Dick Scobie, former UUSC executive director. “They did interviews with people on the street-corner level during the 1974 busing crisis.” In Mississippi, UUSC supported the Mississippi Audio Visual Rural Information Center in rural Rankin County, where residents used video and cable access to discuss local issues and share information. Di Figlia notes the impact: “The project worked to fill serious information gaps, break down a sense of isolation and encourage grassroots organizing for change.”

2009–10, Northern Uganda

In 2008, over 1.8 million Acholi people in rural northern Uganda had been displaced for up to 20 years as a result of the brutal war between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Ugandan government. As part of a program that helped over 20,000 people return home, UUSC worked with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology D-Lab to help the Acholi people implement innovative, cost-effective, and relevant technologies to improve their lives.

A key concern of Caritas Pader, UUSC’s on-the-ground partner, was to ease women’s burdens — including fetching water, hand-milling grains, and seeking household fuel — that deprived them of economic opportunities and kept girls out of school. With that in mind, Amy Smith, D-Lab’s founder and codirector, conducted a series of trainings with UUSC in two large transition camps to transform community members’ ideas into practical realities.

The result: foundational skills for developing and implementing low-cost and sustainable technologies that could be produced locally, reduce work burdens, and conserve the environment. Participants produced biomass charcoal from agricultural waste and created practical tools like a thresher, nut sheller, water cart, and mechanized tool sharpener with locally available materials. Jackie Okanga, coordinator of UUSC’s work in Uganda, on the impact of the trainings: “Not only has this helped them reduce their workload, it has also been an income-generating activity.”

1949, Germany

In the wake of World War II, the Unitarian Service Committee (USC) partnered with Arbeiter Wohlfahrt, an organization that USC had worked with to support homes for displaced children, to develop a pioneering social work education program. Spearheaded by USC staff member Helen Fogg, the program began in 1949 with a summer institute in child care that kicked off USC’s 20-year commitment to social work education.

The summer institutes featured participatory sessions grounded in USC’s democratic, case-work teaching approach. In addition to gaining new skills to bring to their work and communities, attendees also went on to train others in the skills they learned. As told in Roots and Visions, Katherine Taylor, who led the institute staff for five summers in a row, reflected on the experience of institute participants:

“By degrees the participants realized that we wished to learn from them and to learn about them as individuals. Once they felt released for real talk, the floodgates were opened; we were swept up in the problems of the troubled people of all ages for whom they were responsible, behavior problems of children in institutions, or adolescents in barrack camps, and difficulties of staff relationships within the agencies. We worked entirely in the context of the German scene. In discussing an emotionally disturbed child, what was the use of suggesting, ‘Refer him (or her) to a child guidance clinic and assign a psychiatric social worker to work with the parents,’ when there was no clinic in our sense of the word and no psychiatric social worker? Instead, we discussed what might have caused the child to become so disturbed — what about his parents, school, the neighborhood in which he lives, the family’s experience during the war? And then, how can one best help?”

The inaugural social work education program was a huge success, which led to the funding of additional similar programs by the U.S. State Department and the Ford Foundation. One such program was the Bremen Neighborhood House, where the approaches to social work taught in the USC institutes were put into action and which grew to include 24 community houses providing a wealth of services. USC began fielding requests for social work education and training from institutions in Greece and Korea, and Fogg worked to develop and adapt the program to fit various cultural environments.

2012–present, United States

UUSC once had a Human Rights Education Department, which produced A Journey to Understanding, a comprehensive study and action guide on Central America that fueled UU involvement in the 1980s, as well as Promise the Children, a guide published in 1989 on the needs and rights of children at risk. That educational legacy is carried on today through the Unitarian Universalist College of Social Justice (UUCSJ), a collaboration of UUSC and the Unitarian Universalist Association. UUCSJ helps Unitarian Universalists deepen and sustain the work of justice in their congregations and communities.

Since the college launched in 2012, more than 500 people have participated in UUCSJ’s transformational programs. These educational programs and service-learning journeys help people cross boundaries and imagine new ways to bring their faith together with their yearning to make a difference in the world.

Each UUCSJ program utilizes the UUCSJ Study Guide for Cross-Cultural Engagement, an online resource released in early 2014 and designed to help participants better understand the dynamics of race, class, power, and privilege in their own lives and in the lives of the partners they visit on experiential learning journeys. In service of creating better allies and activists, the study guide explores three central questions:

- How can you make sense of your experience as you go?

- What does it mean to be an ally to the struggles you witness?

- How can you be a more effective activist for justice when you come back home?

In addition to the study guide, UUCSJ has expanded its resources to include shorter issue-specific study sessions designed to take people deeper into their program areas. The study resources support people returning from a UUCSJ program in sharing what they’ve learned with their communities; the resources also support people who are not connected to a program but want to explore with others the complex issues of climate justice, immigration justice, and indigenous rights.

As Kathleen McTigue has written, these study resources help participants “gain new insight about the root causes of injustice and discover new ways to respond as global citizens and people of faith.”

Inspired by these stories? Make a gift to UUSC today! And explore UUSC’s 75th anniversary page.