The Unitarian Universalist Service Committee advances human rights through grassroots collaborations.

By on December 13, 2018

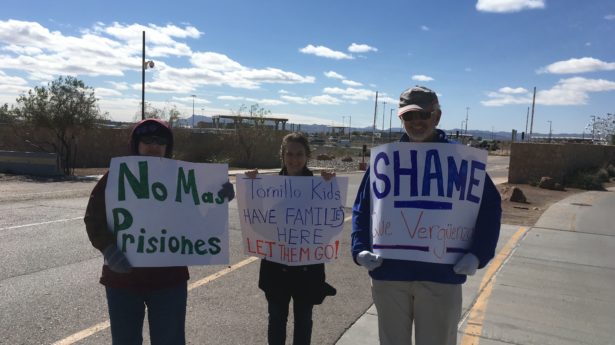

Part 3: Militarization and Resistance

November 6, 2018 was Election Day, and there was a strong buzz of excitement and worry in the air of El Paso. Texas’s first viable Democratic candidate for Senate in decades, Beto O’Rourke, was a native of El Paso and beloved to many in the local community. Simultaneously, the Border Patrol and U.S. Military troops dispatched to the border were preparing for a “crowd control simulation,” citing the pending arrival of the migrant caravan at the railroad crossing near the international bridges between El Paso and Tijuana donning riot gear, rifles, and batons. Less than a half mile from a polling station, in an almost entirely Latinx neighborhood, on Election Day.

Public outcry about potential voter intimidation was successful, and the training exercise was cancelled for Election Day and moved three days later to that Friday, November 9. As the “operational readiness exercise” went ahead on Friday, it was closed to the press but visible to the public eye: an overwhelming scene of riot gear, a helicopter overhead, agents on horseback, and military armored vehicles shutting down the busy Paso Del Norte international bridge.

On Saturday morning, I made my way to San Jacinto Plaza, already decorated for the holidays, to join more than 100 members of the community gathered in protest against the militarization of the place that they call home, organized by the Border Network for Human Rights. As we marched through the streets carrying white crosses with the names of those who have died trying to cross the border, everyone from kids in strollers to elderly couples joined in chanting: “Aquí en la frontera/No es zona de guerra” (This is not a war zone here on the border).

The march ended across from the main international bridge between El Paso and Ciudad Juarez. Every speaker was interpreted between English and Spanish to accommodate the diverse crowd. The event’s host began, “We are spending $200 million for the deployment of soldiers here. This is our America. Soldiers on the border against the grand enemy: children, mothers, young people. Where Trump puts soldiers, we will extend our hand. There is no crisis here except the one that has been created.”

A young leader from the Detained Migrant Solidarity Committee spoke: “This is an effort to intimidate our community, to make us believe that we are against each other. A lot of the people coming are being pushed from their lands, the same way that Native peoples here were pushed from their lands.”

As the rally dispersed and I walked away, passing the Port of Entry, I thought about the people who spent weeks waiting on the other side of the bridge over the Rio Grande. Asylum-seeking families had camped out day and night, waiting for their turn to present themselves for asylum and be detained, until earlier that week when they were forcibly removed and told that they’d only be considered for asylum if they relocated to the Casa Migrante shelter, a significant drive away from the border itself. A new system was announced: Each day at the shelter, between 12 and 20 people would be allowed to apply for asylum in the United States, and a van will take them from the shelter to the Port of Entry. They called this “metering.”

In order to keep track of the list, parents at the shelter had numbers written in black sharpie on the inner wrist of their arms.

Photo Credit: Hannah Hafter