The Unitarian Universalist Service Committee advances human rights through grassroots collaborations.

Partner Profile: Center for Human Rights and Environment

April 9, 2015

Ever heard of a “cryoactivist”? In the words of the Center for Human Rights and Environment (CEDHA) in Argentina, it’s “someone who protects the icy resources of our planet,” particularly glaciers and permafrost areas that are endangered by changing weather patterns and mining operations. The cryoactivists at CEDHA have been teaming up with UUSC to take on the challenge of climate change and its affects on the environment and the human right to water.

CEDHA has been working at the intersection of environmental concerns and human rights on local and national levels since 1999. As they put it, “[CEDHA] is dedicated to building a more harmonious relationship between the environment and people, defending human rights, strengthening public policy and ensuring access to justice for victims of environmental degradation.”

“They were one of the few Latin American groups working on the human right to water, from a legal strategy, at the time we started partnering with them,” says Patricia Jones, UUSC’s senior program leader for the human right to water. When CEDHA became a UUSC partner in 2007, UUSC was the only funder of their human right to water program, which was doing groundbreaking work in the arenas of litigation and legislation.

Setting legal precedent and ensuring real access to clean water

On the litigation side, UUSC worked with CEDHA on the Chacras de la Merced case, which successfully set a legal precedent requiring that the human right to water be ensured in Argentina. The case involved the small community of Chacras de la Merced, whose residents relied on groundwater wells for their water. Polluted river water from the nearby city of Cordoba — which was allowing factory runoff and the dumping of its own sewerage into the river — contaminated the wells and made residents’ only source of clean water untenable.

As Jones explains, “When we support litigation, we use screening questions of ‘what’s going to help someone on the ground immediately? Is this case going to actually mean someone’s life changes?’” It certainly did in the Chacras de la Merced case: as a result of the lawsuit, Cordoba was ordered to pay for and deliver clean water to the residents of Chacras de la Merced.

Protecting glaciers to protect a human right

Passage of the Argentine National Glacier Protection Law is another landmark project that UUSC has supported with CEDHA. The first glacier protection legislation in the world, this law was first passed in 2008 but was then vetoed by the Argentinian president. CEDHA and UUSC weren’t ready to give up on the affectionately titled “human right to the glacier,” though. After another intensive advocacy push, the law passed again successfully in 2010, without veto, and is now being implemented.

But why glaciers? What do they have to do with human rights? As CEDHA reports, “Of the 2% of available freshwater, ¾ of it is in ice form. That is, most of our available freshwater is in conveniently stored glaciers. It is well known that recent climate change trends are affecting our global environment, placing our atmosphere and global ecological stability at risk. Melting glaciers are a well-documented impact of this climate trend.” Once glaciers are gone, damage to this major source of freshwater — which humans need to survive and access to which is a human right as defined by the United Nations — will be irreversible.

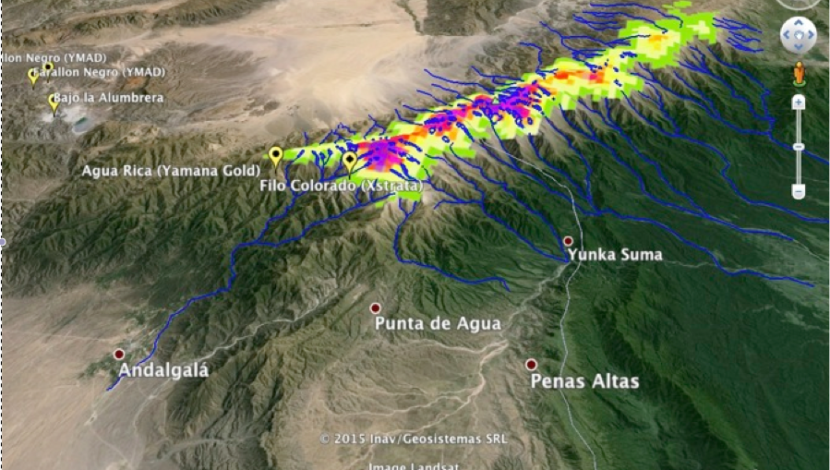

The glacier protection law is an incremental reform that requires a higher level of environmental impact assessments from any company that wants to operate in glacier zones and surrounding areas. Implementation of the law involves inventorying glaciers and studying them to show the impacts from mining operations and changing climate.

Community education has also been a major component of this work. As CEDHA explains, “Glaciers need to be at very high or very cold altitudes to survive, where humans generally don’t wander and much less live. In the end, we don’t legislate and don’t protect what we don’t know or understand.”

While this law applies to Argentina, it could have a far greater reach. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights takes regional laws and decisions into consideration when making rulings, and this law will hopefully be the first of many dedicated to protecting precious water resources throughout the Americas. To spread the word and inspire budding cryoactivists worldwide to push for similar advancements, Jorge Daniel Taillant, CEDHA’s executive director, has authored Glaciers: The Politics of Ice, forthcoming from Oxford University Press.

Lessening — and sharing — the burdens

Looking forward, CEDHA is strategizing about how to stop fracking, the practice that uses inordinate amounts of water — and poisons nearby groundwater — to release oil or natural gas from rock beds. Fracking is just starting to infiltrate Argentina, and along with it comes the dangers of water waste and contamination. Jones says, “Almost everything in our lives — this pen, this paper — passes the burden of its production onto local communities in the form of contaminated drinking water.” The energy that ultimately comes from fracking is no exception.

When local communities bear the burden of production, it’s people on the margins — indigenous people, low-income people, and people of color, for example — who actually pay the price. And that is one reason UUSC partners with CEDHA. As they see it, “CEDHA works to protect human rights of vulnerable communities affected by environmental contamination, particularly contamination to water resources, which are perhaps the most important and critical natural resources for human survival and human health. Contamination to drinking water is one of the most significant and troubling impacts to low-income human settlements.” UUSC’s work with CEDHA is about lessening — and equitably sharing — the burdens that unbridled, irresponsible human consumption, in large part by the most privileged residents of this planet, have brought forth.